- News

A Visit to Glasgow Mushroom Company

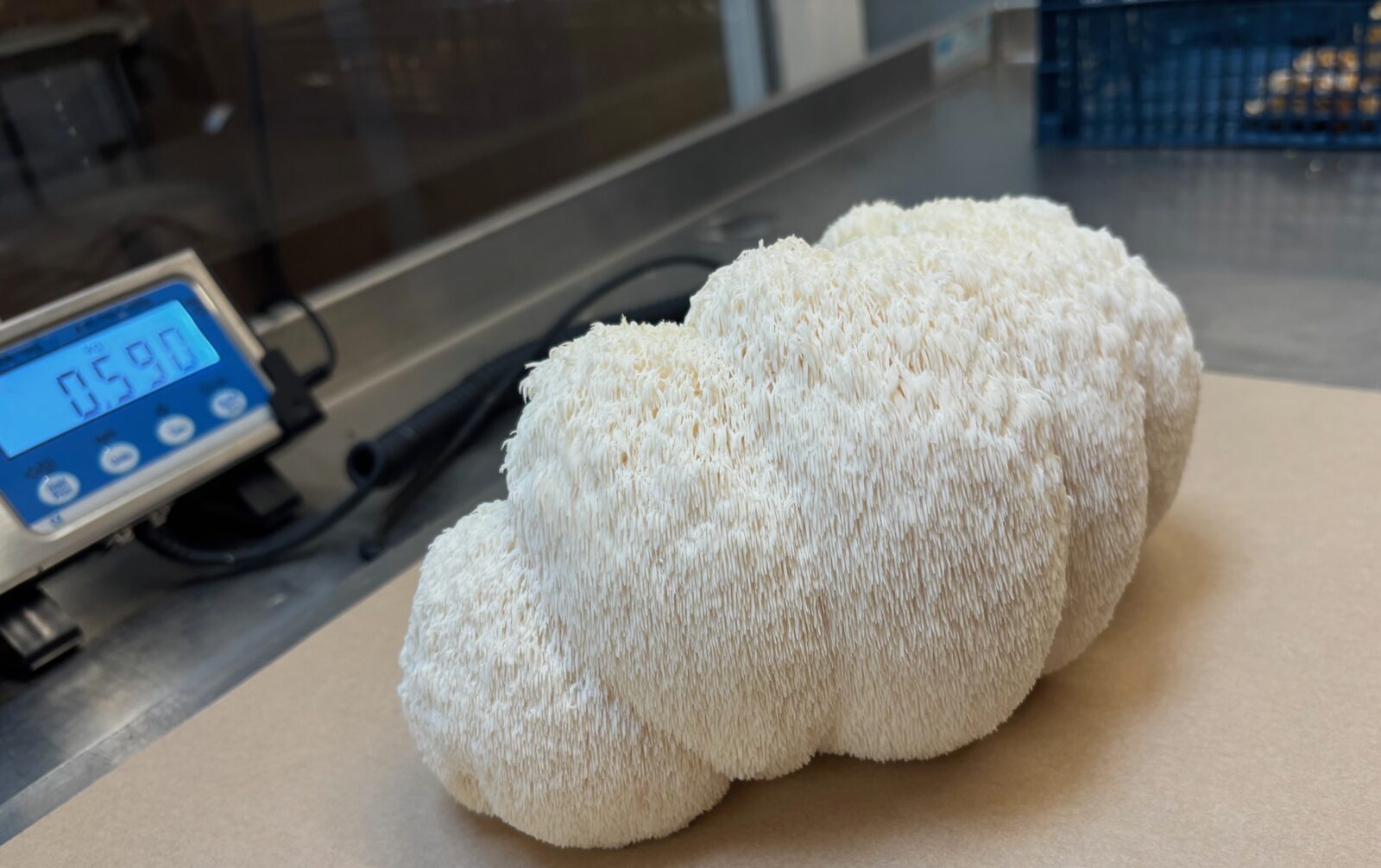

Tucked away in an industrial park between the River Kelvin and the Forth & Clyde Canal, is Glasgow City’s most productive farm. Purveyors of speckled chestnut, grey oyster, and lion’s mane mushrooms, this is Glasgow Mushroom Company. Founded by Hendrik Mans and Harriet Sinclair, they produce 50 kilograms of mushrooms per week. This supply goes directly into Glasgow shops and restaurants via B2B sales. Demand is exploding. But back in 2019 when they started, there was little interest in gourmet mushrooms beyond Oysters. No one was talking about mushrooms, and people said it would never work. So how did they get here? Hendrik took me for a walk around their facility and gave me the run down.

A bit of back story

Let’s rewind a bit. Hendrik, a South African native, moved to the UK in secondary school. He took International Business Studies at university in Sheffield but, by his account, he wasn’t exactly focused on studying. With a friend, he started fixing computers for students and businesses. They were successful enough that a larger company bought them out. This gave Hendrik a taste of entrepreneurship, and he began casting around for the next business idea.

He grinned as he told me his thought process: ‘internet- that’s come and gone; green energy, I’m too late…what’s the next big thing?’ He decided that food security was a huge concern and would only become more pressing. He continued his business studies, now with a focus on horticulture, taking a master’s from Writtle University College in Essex, with a semester abroad in the Netherlands, and then carrying out his dissertation on post-harvest agribusiness in Kenya. One of the key concepts centred around calories- specifically that there were two ways of getting calories into people:

- Foreign production for local consumption

- Local production for local consumption

His studies were clearly entrenching the former over the latter, even while teaching that international food supply chains require 27 calories of energy to deliver 1 calorie of nutritional value to a human.

Why mushrooms?

Hendrik concluded that to make the biggest impact on food security, local production for local consumption was the way forward. He could apply his business studies to change the system for the better. At that point, ‘a lot of people said that getting into urban farming is extremely expensive.’ So, he looked for the highest value sold, with the lowest value input, and the lowest capital requirements, and determined that mushrooms were a good bet.

He took a growing assistant job at the Leckford Estate in Hampshire, growing mushrooms in a controlled environment for John Lewis & Partners. As a self-proclaimed wolf in sheep’s clothing, he brought new ideas and ways of growing and soon became the business development manager. Living as simply as possible, Harriet and Hendrik saved for five years until they were ready to strike out on their own. They moved up to Scotland, where Harriet has family connections, settling in Glasgow, where there were exactly zero gourmet mushroom companies.

Into the farm

Wandering through the farm is not what you expect. It’s indoor for one, a single unit in a row of light industrial warehouses, with neighbours focused on precision engineering and audio-visual equipment. But it’s not like a vertical farm with robots harvesting the produce and all the workers in hazmat suits. Hendrik strolls casually through in shorts and polo showing off the inoculation and fruiting chambers, and the climate control systems he engineered. A bucket keeps hissing and releasing steam. A salvaged tumble dryer is used to mix the spawn into the substrate. In the concrete back yard, Harriet meets a couple with a trailer hitched to their small hatchback, who have come to collect spent mushroom substrate.

They are upgrading the facility slowly but surely and, in the previous 12 weeks before my visit, they have moved from producing 20kg mushrooms/week to 50, and plan to reach 90kg/week soon. Hendrik says that industrial contacts and access to capital markets have allowed them to invest in the business. By upgrading the facility, they plan to reach up to 150kg/week by the same time next year. Staying true to local production for local consumption, most of this supply is sold straight into Glasgow’s stores and restaurants. ‘We are small but doing things in the same way as big farms.’

The process

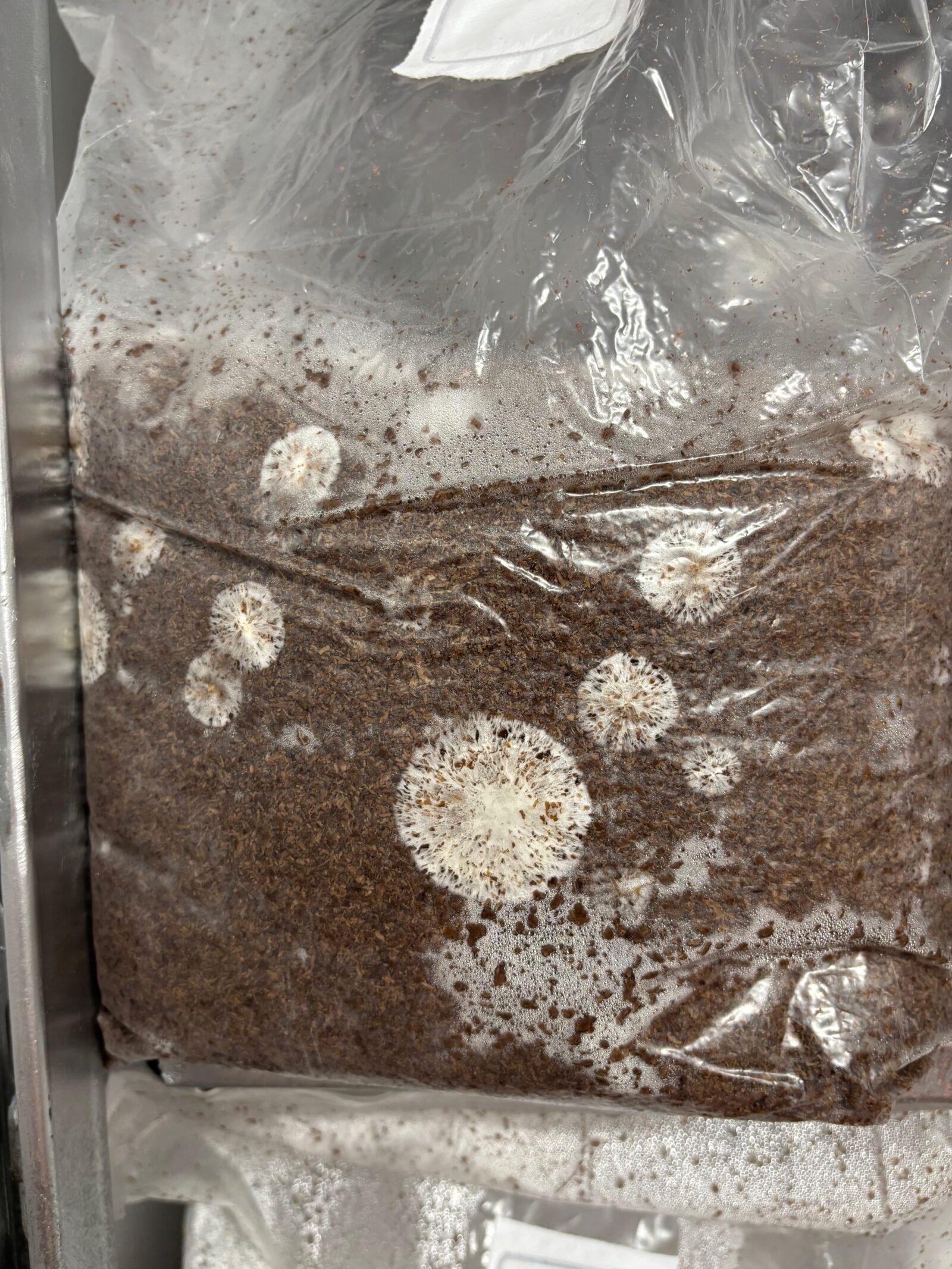

The liquid culture containing the mycelium is added to millet to create an intermediary inoculant known as spawn. The substrate (already heat-treated) is then mixed and fills a 4.5kg autoclavable bag. Each bag has a filter patch which allows air to pass through but prevents airborne microbes, spores of competing fungi and bacteria from entering. To get the fungi into each bag, it is inoculated with the spawn, the millet acting as little life rafts for the fungi. Measured amounts of inoculant are given to each bag in a clean room environment and the bags are sealed. They are then tumbled to distribute the spawn evenly amongst the substate in the bag. Next it goes into the incubator where the fungus is free to colonise and make its home. Once fully colonised, the bags are moved to the fruiting chamber, where baby mushrooms, known as pins, start emerging. Each bag can be

harvested four times, before the substrate is exhausted. The whole process is done by hand and takes about a month from sterilisation of the substrate to final harvest.

What to do with the spent substrate

The substrate might be exhausted but it’s not done yet… Each kilogram of mushrooms harvested produces 5kg of spent substrate. While most of the nutrition has gone into the mushrooms, the remaining substrate has a high carbon content, is pH neutral and works great as brown matter for compost, or as a soil conditioner. GMC offers this spent substrate free for personal and community use via their Compost Club.

Side business- Caledonian Mushroom Company

The next frontier is selling their own substrate. Currently, GMC buys in hardwood pellets and soybean hulls from the EU, part of the Masters Mix used by 99% of commercial growers. They mix the substrate in house, whereas a lot of other farms that fruit mushrooms buy it pre-mixed. The hardwood pellets and soybean hulls are mixed 50/50 to create the substrate. Soybeans come with their own environmental concerns so Hendrik would like to replace them with oat bran from Scotland. While the oat bran is more expensive, the mix is 80:20 wood pellets : oat bran, so the actual cost difference is negligible.

By removing soy from the process, they also remove the potential for gluten contamination that Hendrik says is a concern: ‘We would like to be gluten free to make the farm safe for Harriet and others who have coeliac.’ This is also why they switched from rye grain to millet for their spawn. ‘It’s mostly to ensure no gluten-containing dust gets up and settles on stuff in the farm.’ As for the wood- they would like to switch to sourcing shavings from a local supplier that specialises in hardwood.

This emphasis on quality control and refinement to the production process ensures that they are moving toward a product with no animal, peat, gluten, soy or imports at any point in its production. The idea is to sell this Scottish-sourced, low-impact substrate directly to other mushroom growers in Scotland and the UK. As Hendrik points out, ‘there are few suppliers who do this in the UK and none in Scotland.’

What’s next

Besides scaling up production, and branching out into supplying substrate, GMC also has big plans for becoming more circular with their heat and energy supply. Solar panels will provide low carbon electricity, and a heat pump will help capture waste heat from the sterilisation and incubation processes and use it to heat the fruiting chambers in winter. In the meantime, you can try their delicious mushrooms. Look out for GMC mushrooms at a greengrocer near you, find them at a farmers’ market, or reach out to them to source some spent substrate for your next growing project.